(Submitted for publication in the UMA Bulletin; I am an Editorial Board member.)

“Overdosed America” is a book by Dr. Abramson that documents how doctors are prescribing too many drugs. The Journal of the American Medical Association published an article on February 25th 2009 agreeing with the good doc.

Before you assume that I am blaming doctors let me say that in my opinion they are mostly victims as much as the patients who receive our prescriptions. Of course we all share a bit of the responsibility for the drugging of our society. Doctors have not made a significant effort to learn to treat the roots of diseases (nutrition, environment and Mind-Body-Spirit issues) and patients have grown to expect a pill to manage their every little symptom.

Doctors may excuse themselves by saying that their patients’ genetics are so strong that nothing will change their patients’ tendency to develop a given disease. This is an indefensible position when we study the fields of nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics; yes, nutrition does modulate genetic expression. In fact, toxic environments and relationships also modulate genetic expression.

Patients may excuse themselves by saying it is too hard to change their lifestyle (an opinion shared by most doctors); they just want the latest pill they saw advertised on TV. In fact, in my own practice I have seen patients who feel I don’t listen to them because I don’t prescribe them the latest drugs advertised on TV for their symptoms nor thyroid and sex hormones, amphetamines and the newest psychoactive medications to help them lose weight. Rather than listen to my advice to change their diets, detoxify their environments and their relationships they find a practitioner next door who will eagerly pull out his/her smoking prescription pad.

For these and many other obvious reasons I rejoice in the JAMA’s courage to publish the article “Promoting More Conservative Practices.” So that you rejoice with me I am herein quoting from this article. The implications of the following statements are enormous:

• “Although medical and pharmacy curricula and journals are rich with information about drugs and treatment of specific diseases, there is a paucity of education on ways to become effective lifetime prescribers. Two recent reports from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) lamented the current state of pharmacology teaching and the disturbing extent of pharmaceutical industry influence at all stages of medical education. Given the well-documented prevalence of medication-related harm and inappropriate prescribing, such educational reform is necessary but not sufficient to ensure that patients are optimally treated… trainees need guiding principles to inform their thinking about pharmacotherapy to help them become more careful, cautious, evidence-based prescribers.”

• “These lessons are fundamental for teaching clinicians how to develop excellent prescribing skills, yet such fundamentals are absent or underempahsized in current medical pharmacy education… they also need to be taught a set of skills and attitudes that will help them approach claims for drugs, especially new drugs, more critically.”

• “Without a more cautious and more skeptical approach to using drugs, prescribers will lack the will and the skills to resist ubiquitous promotional messages encouraging them to reach for newer and often more expensive medications.”

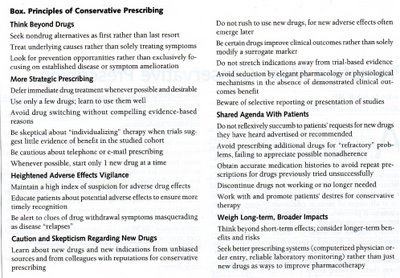

• “Although the attitudes and behaviors recommended in our principles [see box below] should not be terribly controversial, taken together they represent a departure from current practice.”

• “From the founder of modern medicine Dr Osler to leading pharmacology textbooks, taking a more skeptical and conservative approach to pharmacotherapy has a long and honorable history in medicine… Rather than therapeutic nihilism, the approach of these guidelines aims to better respect the limitations of knowledge and more closely align clinicians with the interests of patients.”

Many doctors reading this article are dedicated to these simple principles. While not perfect in their prescribing I would guess they strive to follow the old dictum “primum non nocere” (first do no harm) to the best of their abilities.

Of all the recommendations in the box I would like to emphasize the first 3 under “think beyond drugs.” Many doctors reading this article no doubt have had these simple principles and their desire to implement the best ways to heal patients as the driving forces behind their pursuit of research highlighting nutrition, environmental issues and the Mind-Body-Spirit connection. In my own experience, applying the references I have found in our leading medical journals have helped me avoid and/or stop 80% of the prescription medications commonly used for chronic ailments, a figure that Dr Willet at Harvard Medical School has also documented.

More evidence

Interestingly, the same issue of the JAMA had related articles on how clinical practice “guidelines” are influenced by marketing more than hard evidence and how the “FDA exerts too little oversight of researchers’ conflicts of interest.” The article on the controversy surrounding the cholesterol lowering drug exetimibe/simvastatin is a good example of how prevention and nutrition are seldom part of serious discussions on treating heart disease.

The New England Journal of Medicine last month had an article along the same lines, “The Neurontin Legacy: marketing through misinformation and manipulation.” Before tackling the well-known drug neurontin/gabapentin, the article opens up by reminding us of the shady deals that allowed synthroid-makers to hide evidence that the generic levothyroxine is just as good. Then, it gives pointed examples and direct quotes from pharmaceutical executives who pushed their representatives to drive up sales by hyping neurontin to doctors. The drug reps claimed the drug had benefits that were never shown in their internal research.

The author feels that “drastic action is essential to preserve the integrity of medical science and practice and to justify public trust” and that the public and doctors need “public funding of peer-reviewed pharmaceutical research through a National Institute for Pharmaceutical Research that might be funded by a tax on all drug sales.”

I am sure you will agree with his final conclusion:

“Will our profession soon feel compelled to advocate for such actions to preserve our integrity, our social contract and ultimately our privileges?”

Perhaps the article in the same issue of the NEJM may help us shed some light on the “man behind the curtain:” “Money and the Changing Culture of Medicine.” Again, the article’s implications are so enormous that I choose to only quote from it:

This is the title of a remarkable article in the top medical journal in the world Here are its main points:

• “Assigning a monetary value to every aspect of a physician’s time and effort may actually reduce productivity, impair the quality of performance and thereby increase costs.”

• “Even the suggestion of money promotes behavior marked by selfishness and lack of collegiality.”

• “Medicine has marketplace elements that are inherent in any business-a physician receives payment for services. But there is also a communal relationship, an expectation and obligation to help when assistance is needed. In the current environment the balance has tipped toward market exchanges at the expense of medicine’s communal dimension. Many physicians we know are so alienated and angered by the relentless pricing of their day that they wind up having no desire to do more than the minimum required for the financial bottom line.”

The journal feels that the answer is “Patient-centered medical home,” or a “compassionate partnership…. [where] the insurer would pay a set fee for each patient cared for in the medical home to cover what is now not reimbursed time.” In my opinion this means that doctors would now have an incentive to learn about nutrition and motivational techniques to help patients change their toxic lifestyle. This would lead to more emphasis on prevention and a significant reduction in the cost of health care.

“Caregivers should be appropriately reimbursed but should not be constantly primed by money. Success in such a model will require collegiality, cooperation and teamwork-precisely the behaviors that are predictably eroded by a marketplace environment.”

The bottom line is money.

As the economy continues its downward spiral I cannot get enough reading in Economics. The last book I read was Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith (1776.) I highly recommend it, if you are willing to speed-read through the boring parts. The two things that struck me the most was his common sense and wisdom and how both sides of the political/economic spectrum misquote him to justify their own ideologies.

The supply siders (Republicans) emphasize how the invisible hand is going to take care of practically every thing while the demand siders (Democrats) emphasize government regulation. It turns out that Adam Smith wrote that both are necessary: business can only thrive when the law efficiently protects the right of business people to seek profits, but with the limitations necessary to respect labor and the land.

One thing is certain, says Adam Smith: when business people gather, they will always have the tendency to organize themselves to maximize profits even at the expense of the public. This is why regulation is necessary. And regulation of the pharmaceutical industry, particularly of their CME tactics and advertisement is sorely needed.

“The profession of medicine, in every aspect, clinical education, and research, has been inundated with profound influence from the pharmaceutical and medical device industries. This has occurred because physicians have allowed it to happen, and it is time to stop.”

Despite the clear and common sense advise from Adam Smith we will always be polarized when it comes to politics and economics. You would think that anyone interested in scientific reasoning would seek the middle ground he championed. But, it is not inherent in most people to think scientifically or objectively. This is why I enjoyed the article “On Second Thought…”

“When politicians [change their mind], they are tarred as flip-floppers. When lovers do it, we complain they are fickle. But scientists are supposed to change their minds when evidence undercuts their views. Dream on…But really, we shouldn’t be surprised. Proponents of a particular viewpoint, especially if their reputation is based on the accuracy of that viewpoint, cling to it like a shipwrecked man to flotsam. Studies that undermine that position, they say, are flawed.”

Which brings me back to us, doctors. You would think that most of us would be ready and excited to accept the scientific evidence in medical journals that highlights prevention, nutrition environmental toxins and the Mind-Body –Spirit connection. But, it seems that the scientific inquiry required to take the time is not in abundant supply. Could it be that Thomas Kuhn was right when he said that a scientific paradigm (i.e., “nutrition is a second class alternative”) topples when the last of its powerful adherents dies? Could it be that money has something to do with what scientists/doctors believe?