7/13/2020

A woman not wearing a mask walked up to another wearing one and proceeded to heavily breathe in her face. The victim made the news pleading for people to wear a mask for the sake of vulnerable people, like her immuno-compromised daughter at home. Watching the report, I tried to understand why the perp did that. Having recently read John Stuart Mills essay on LIBERTY, I understand that governments should not interfere with our rights to live as we please. However, there is a generally accepted constraint on that inalienable right: the wellbeing of the society we live in. We do not have the freedom to behave in a way that will hurt our fellowman.

Was the anti-mask woman mentally ill? Or a fanatical ideologue? Or both? Did she not care that our amazing, overwhelmed, courageous health workers are on their knees begging us to wear masks? Is that woman willing to take the chance that full hospitals may only have a measly cot in the parking lot for her?

I strive to live by John Stuart Mill’s advice on Liberty: “He who knows only his side of the case knows little of that… He is a stranger to that portion of the truth that is only known to those that who have attended equally and impartially to both sides and endeavored to see the reasons of both in the strongest light.”

J.O. YGasset’s words are also relevant here: “People force us into actions that proceed from them, and not from us… Many thoughts, ideas and opinions we have never thought on our own account, with full and trustworthy evidence of their truth; we think them because we have heard them and we say them because ‘they are said.’”

With so much uncertainty and politics, I say let us rely on science and facts, as subjective as they may be at times. What else can we do?

References

AMA, other medical groups urge Americans to wear face masks

Politico (7/6, Cohen) reports a letter signed by the American Hospital Association, the American Medical Association, and the American Nurses Association said, “This is why as physicians, nurses, hospital and health system leaders, researchers and public health experts, we are urging the American public to take the simple steps we know will help stop the spread of the virus: wearing a face mask, maintaining physical distancing, and washing hands.” HealthDay (7/6, Preidt) reports that the groups wrote that Americans “are not powerless in this public health crisis, and we can defeat it in the same way we defeated previous threats to public health – by allowing science and evidence to shape our decisions and inform our actions.” HealthLeaders Media (7/6, Blackman) reports that the letter said, “Moving forward, we must all remain vigilant and continue taking steps to mitigate the spread of the virus to protect each other and our loved ones. There is only one way we will get through this – together.”

Reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2

J. Science 26 Jun 2020:Vol. 368, Issue 6498, pp. 1422-1424

Respiratory infections occur through the transmission of virus-containing droplets (>5 to 10 µm) and aerosols (≤5 µm) exhaled from infected individuals during breathing, speaking, coughing, and sneezing. Traditional respiratory disease control measures are designed to reduce transmission by droplets produced in the sneezes and coughs of infected individuals. However, a large proportion of the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) appears to be occurring through airborne transmission of aerosols produced by asymptomatic individuals during breathing and speaking (1—3). Aerosols can accumulate, remain infectious in indoor air for hours, and be easily inhaled deep into the lungs. For society to resume, measures designed to reduce aerosol transmission must be implemented, including universal masking and regular, widespread testing to identify and isolate infected asymptomatic individuals.

Humans produce respiratory droplets ranging from 0.1 to 1000 µm. A competition between droplet size, inertia, gravity, and evaporation determines how far emitted droplets and aerosols will travel in air (4, 5). Larger respiratory droplets will undergo gravitational settling faster than they evaporate, contaminating surfaces and leading to contact transmission. Smaller droplets and aerosols will evaporate faster than they can settle, are buoyant, and thus can be affected by air currents, which can transport them over longer distances. Thus, there are two major respiratory virus transmission pathways: contact (direct or indirect between people and with contaminated surfaces) and airborne inhalation.

In addition to contributing to the extent of dispersal and mode of transmission, respiratory droplet size has been shown to affect the severity of disease. For example, influenza virus is more commonly contained in aerosols with sizes below 1 µm (submicron), which lead to more severe infection (4). In the case of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), it is possible that submicron virus-containing aerosols are being transferred deep into the alveolar region of the lungs, where immune responses seem to be temporarily bypassed. SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to replicate three times faster than SARS-CoV-1 and thus can rapidly spread to the pharynx, from which it can be shed before the innate immune response becomes activated and produces symptoms (6). By the time symptoms occur, the patient has transmitted the virus without knowing.

Identifying infected individuals to curb SARS-CoV-2 transmission is more challenging compared to SARS and other respiratory viruses because infected individuals can be highly contagious for several days, peaking on or before symptoms occur (2, 7). These “silent shedders” could be critical drivers of the enhanced spread of SARS-CoV-2. In Wuhan, China, it has been estimated that undiagnosed cases of COVID-19 infection, who were presumably asymptomatic, were responsible for up to 79% of viral infections (3). Therefore, regular, widespread testing is essential to identify and isolate infected asymptomatic individuals.

Airborne transmission was determined to play a role during the SARS outbreak in 2003 (1, 4). However, many countries have not yet acknowledged airborne transmission as a possible pathway for SARS-CoV-2 (1). Recent studies have shown that in addition to droplets, SARS-CoV-2 may also be transmitted through aerosols. A study in hospitals in Wuhan, China, found SARS-CoV-2 in aerosols further than 6 feet from patients, with higher concentrations detected in more crowded areas (8). Estimates using an average sputum viral load for SARS-CoV-2 indicate that 1 min of loud speaking could generate >1000 virion-containing aerosols (9). Assuming viral titers for infected super-emitters (with 100-fold higher viral load than average) yields an increase to more than 100,000 virions in emitted droplets per minute of speaking.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for social distancing of 6 feet and hand washing to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2 are based on studies of respiratory droplets carried out in the 1930s. These studies showed that large, ∼100 µm droplets produced in coughs and sneezes quickly underwent gravitational settling (1). However, when these studies were conducted, the technology did not exist for detecting submicron aerosols. As a comparison, calculations predict that in still air, a 100-µm droplet will settle to the ground from 8 feet in 4.6 s, whereas a 1-µm aerosol particle will take 12.4 hours (4). Measurements now show that intense coughs and sneezes that propel larger droplets more than 20 feet can also create thousands of aerosols that can travel even further (1). Increasing evidence for SARS-CoV-2 suggests the 6 feet CDC recommendation is likely not enough under many indoor conditions, where aerosols can remain airborne for hours, accumulate over time, and follow airflows over distances further than 6 feet (5, 10).

Infectious aerosol particles can be released during breathing and speaking by asymptomatic infected individuals. No masking maximizes exposure, whereas universal masking results in the least exposure.

In outdoor environments, numerous factors will determine the concentrations and distance traveled, and whether respiratory viruses remain infectious in aerosols. Breezes and winds often occur and can transport infectious droplets and aerosols long distances. Asymptomatic individuals who are speaking while exercising can release infectious aerosols that can be picked up by airstreams (10). Viral concentrations will be more rapidly diluted outdoors, but few studies have been carried out on outdoor transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 can be inactivated by ultraviolet radiation in sunlight, and it is likely sensitive to ambient temperature and relative humidity, as well as the presence of atmospheric aerosols that occur in highly polluted areas. Viruses can attach to other particles such as dust and pollution, which can modify the aerodynamic characteristics and increase dispersion. Moreover, people living in areas with higher concentrations of air pollution have been shown to have higher severity of COVID-19 (11). Because respiratory viruses can remain airborne for prolonged periods before being inhaled by a potential host, studies are needed to characterize the factors leading to loss of infectivity over time in a variety of outdoor environments over a range of conditions

Given how little is known about the production and airborne behavior of infectious respiratory droplets, it is difficult to define a safe distance for social distancing. Assuming SARS-CoV-2 virions are contained in submicron aerosols, as is the case for influenza virus, a good comparison is exhaled cigarette smoke, which also contains submicron particles and will likely follow comparable flows and dilution patterns. The distance from a smoker at which one smells cigarette smoke indicates the distance in those surroundings at which one could inhale infectious aerosols. In an enclosed room with asymptomatic individuals, infectious aerosol concentrations can increase over time. Overall, the probability of becoming infected indoors will depend on the total amount of SARS-CoV-2 inhaled. Ultimately, the amount of ventilation, number of people, how long one visits an indoor facility, and activities that affect airflow will all modulate viral transmission pathways and exposure (10). For these reasons, it is important to wear properly fitted masks indoors even when 6 feet apart. Airborne transmission could account, in part, for the high secondary transmission rates to medical staff, as well as major outbreaks in nursing facilities. The minimum dose of SARS-CoV-2 that leads to infection is unknown, but airborne transmission through aerosols has been documented for other respiratory viruses, including measles, SARS, and chickenpox (4).

Airborne spread from undiagnosed infections will continuously undermine the effectiveness of even the most vigorous testing, tracing, and social distancing programs. After evidence revealed that airborne transmission by asymptomatic individuals might be a key driver in the global spread of COVID-19, the CDC recommended the use of cloth face coverings. Masks provide a critical barrier, reducing the number of infectious viruses in exhaled breath, especially of asymptomatic people and those with mild symptoms (12) (see the figure). Surgical mask material reduces the likelihood and severity of COVID-19 by substantially reducing airborne viral concentrations (13). Masks can also protect uninfected individuals from SARS-CoV-2 aerosols and droplets (13, 14). Thus, it is particularly important to wear masks in locations with conditions that can accumulate high concentrations of viruses, such as health care settings, airplanes, restaurants, and other crowded places with reduced ventilation. The aerosol filtering efficiency of different materials, thicknesses, and layers used in properly fitted homemade masks was recently found to be similar to that of the medical masks that were tested (14). Thus, the option of universal masking is no longer held back by shortages.

From epidemiological data, places that have been most effective in reducing the spread of COVID-19 have implemented universal masking, including Taiwan, Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea. In the battle against COVID-19, Taiwan (population 24 million, first COVID-19 case 21 January 2020) did not implement a lockdown during the pandemic, yet maintained a low incidence of 441 cases and 7 deaths (as of 21 May 2020). By contrast, the state of New York (population ∼20 million, first COVID case 1 March 2020), had a higher number of cases (353,000) and deaths (24,000). By quickly activating its epidemic response plan that was established after the SARS outbreak, the Taiwanese government enacted a set of proactive measures that successfully prevented the spread of SARS-CoV-2, including setting up a central epidemic command center in January, using technologies to detect and track infected patients and their close contacts, and perhaps most importantly, requesting people to wear masks in public places. The government also ensured the availability of medical masks by banning mask manufacturers from exporting them, implementing a system to ensure that every citizen could acquire masks at reasonable prices, and increasing the production of masks. In other countries, there have been widespread shortages of masks, resulting in most residents not having access to any form of medical mask (15). This striking difference in the availability and widespread adoption of wearing masks likely influenced the low number of COVID-19 cases.

Aerosol transmission of viruses must be acknowledged as a key factor leading to the spread of infectious respiratory diseases. Evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 is silently spreading in aerosols exhaled by highly contagious infected individuals with no symptoms. Owing to their smaller size, aerosols may lead to higher severity of COVID-19 because virus-containing aerosols penetrate more deeply into the lungs (10). It is essential that control measures be introduced to reduce aerosol transmission. A multidisciplinary approach is needed to address a wide range of factors that lead to the production and airborne transmission of respiratory viruses, including the minimum virus titer required to cause COVID-19; viral load emitted as a function of droplet size before, during, and after infection; viability of the virus indoors and outdoors; mechanisms of transmission; airborne concentrations; and spatial patterns. More studies of the filtering efficiency of different types of masks are also needed. COVID-19 has inspired research that is already leading to a better understanding of the importance of airborne transmission of respiratory disease.

References and Notes

1. ↵

- L. Morawska,

- J. Cao

, Environ. Int. 139, 105730 (2020).

2. ↵

- E. L. Anderson et al

., Risk Anal. 40, 902 (2020).

3. ↵

- S. Asadi et al

., Aerosol Sci. Technol. 54, 635 (2020).

4. ↵

- R. Tellier et al

., BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 101 (2019).

5. ↵

- R. Mittal,

- R. Ni,

- J.-H. Seo

, J. Fluid Mech. 10.1017/jfm.2020.330 (2020).

6. ↵

- H. Chu et al

., Clin. Infect. Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa410 (2020).

7. ↵

- X. He et al

., Nat. Med. 26, 672 (2020).

8. ↵

- Y. Liu et al

., Nature 10.1038/s41586-020-2271-3 (2020).

9. ↵

- V. Stadnytskyi et al

., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 202006874 (2020).

10. ↵

- G. Buonanno,

- L. Stabile,

- L. Morawska

, Environ. Int. 141, 105794 (2020).

11. ↵

- E. Conticini,

- B. Frediani,

- D. Caro

, Environ. Pollut. 261, 114465 (2020).

12. ↵

- N. H. L. Leung et al

., Nat. Med. 26, 676 (2020).

13. ↵

- J. F.-W. Chan et al

., Clin. Infect. Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa644 (2020).

14. ↵

- A. Konda et al

., ACS Nano 10.1021/acsnano.0c03252 (2020).

15. ↵

- C. C. Leung,

- T. H. Lam,

- K. K. Cheng

, Lancet 395, 945 (2020).

7/06/2020

“Without a certain margin of tranquility, truth succumbs.” J.O. Y Gasset

The COVID-19 pandemic is exposing a lot of PERIPHERAL ISSUES in our society: racism, health care deficiencies, obsolete business practices, sexism, toxic economic and political ideologies. We wonder how we will deal with these issues when things “return to normal.”

I emphasized PERIPHERAL ISSUES because the real problem, the root of our dysfunction, is our inability as individuals to live tranquil, contemplative lives. Our society needs noise and stimulation all day long. If we were able to slow down, smell the roses and have enough down time to look within, we would catch a glimpse of what we really are, spiritual beings caught up in a world that puts material things first. No, I am not a religious person. I don’t go to church. BUT I am certain there is a spiritual realm permeating reality. It does not preclude reason nor scientific thought.

When an army is in disarray and has lost its formation, its only salvation is to “ritornare al segno,” return to the banner. As a society, we need to return to the banner of clear ideas, free of demagoguery and ideologies. There is no idea more basic than understanding WHO WE REALLY ARE.

“Know thyself.”

“Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.” Einstein

Practical application: wear the damned masks!

6/29/2020

Here comes the second wave. Young people are surfing on it, often oblivious to the effect their actions may have on desperate, overwhelmed hospital workers and vulnerable people like their grandma. It is their right, I know. It would be nice if certain politicians provided a better example of following simple instructions such as wearing a mask in public.

CDC estimates that 20 million Americans have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, nearly 10 times as many as the number of confirmed cases

The AP (6/25, Miller, Marchione) reports the CDC estimates “that 20 million Americans have been infected with the coronavirus since it first arrived in the United States, meaning that the vast majority of the population remains susceptible.” The AP adds the CDC’s “estimate is roughly 10 times as many infections as the 2.3 million cases that have been confirmed.” Reuters (6/25, Holland) reports the CDC’s estimate “is based on serology testing used to determine the presence of antibodies that show whether an individual has had the disease.” If the estimate is accurate it would suggest the fatality rate from COVID-19 in the U.S. “is lower than thought.”

Many people with “asymptomatic” coronavirus infections may develop minor lung inflammation, research suggests

NPR (6/23, Huang) reports researchers found many people with “asymptomatic” coronavirus infections “developed signs of minor lung inflammation – akin to walking pneumonia – while exhibiting no other symptoms of coronavirus.” The findings were published in Nature Medicine.

6/22/2020

I still get questions from patients about what to do for the virus. There is a lot of politically-motivated misinformation, causing much confusion and anxiety, especially to the most vulnerable. My advice is simple: trust in the experts, not some obscure guy making a podcast in his mother’s basement.

- Wear a mask when in crowds, indoor shopping or any other place where you cannot avoid close contact with people. Wash your hands often.

- Go back to work if you can abide by the above.

- Get the vaccine when available.

- Do not rely on antibody testing results until said test is more reliable.

- Eat your veggies, avoid processed sugar.

- Take the simplest of supplements: vitamins A-B-C&D.

6/15/2020

Great articles:

Shutdowns prevented 60 million cases of coronavirus in the U.S., research suggests

The Washington Post (6/8, Achenbach, Meckler) reports two studies published in Nature suggest that shutdown orders in China, Europe, and the U.S. prevented many infections. In one study, researchers estimated that “shutdown orders prevented about 60 million novel coronavirus infections in the United States and 285 million in China.” In the other study, “epidemiologists at Imperial College London estimated the shutdowns saved about 3.1 million lives in 11 European countries, including 500,000 in the United Kingdom, and dropped infection rates by an average of 82%, sufficient to drive the contagion well below epidemic levels.”

WHO official says transmission of coronavirus from asymptomatic individuals “appears to be rare”

CNN (6/8, Howard) reports Maria Van Kerkhove, the WHO’s technical lead for coronavirus response and the head of the emerging diseases and zoonoses unit, said the spread of coronavirus by people without symptoms “appears to be rare.” Van Kerkhove said, “From the data we have, it still seems to be rare that an asymptomatic person actually transmits onward to a secondary individual.”

Why a Biologist’s COVID-19 Blogs Went Viral. An Interview With Erin Bromage

Laura A. Stokowski, RN, MS. Medscape June 02, 2020

“When biologist Erin Bromage posted a blog about reducing personal risk for contracting COVID-19, little did he realize that he was about to become very well known. His ability to turn complex scientific principles into clear guidance for action has clicked with millions of people. Medscape spoke with Bromage about the COVID-19 blogs read round the world, and what he foresees for the country moving forward. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Which of your posts got the most attention, and why do you think that happened?

I wrote a post called The Risks – Know Them – Avoid Them. I was writing it for my friends and family in Australia and here in the United States. Both countries were about to reopen, but no one had any idea of where to put our energy with respect to risk mitigation or hazard reduction behavior. So I put together a story: this is what we know, this is what it means, and this is what we can do. It seemed to gel. I think it’s because I could simplify the information that was out there. It’s helped a lot of people visualize the risks. I work in infectious diseases, but mainly with animals. I had been keeping a close eye on the virus since early January. Come February, I started seeing things that made me realize that this is going to change our lives. So I started putting little snippets out to friends on Facebook. After eight or 10 of those posts, one of my friends asked me to put them on a website so everyone could read them.

When I wrote about things like grocery shopping or whether pets can transmit the virus, I’d get a couple of thousand people reading my posts. Then about a month ago I wrote the post about risks, looking at all the data and what it would mean for summer going forward. I posted it on a Wednesday night, and when I woke up in the morning, it had about 8000 views. By the end of Thursday night it was closer to 200,000. I reached out to my university and said, “Help — I don’t know if I’ve done something wrong.” They gave me the help I needed, sort of a buffer around me because I was getting a lot of requests. Over that first weekend it ended up getting seen by 6 million people. The mention in the New York Times made it explode. It’s now had about 18 million views on my site and another 5 to 7 million on hosting sites in different languages.

Your blogs have been praised by neuroscientists, physicians, business owners, teachers, and many others. Yet, you say that you aren’t an expert in these topics. Where do you get your information, and how do you decide what to write about?

No one could possibly claim to be an expert in all the disciplines contributing to the knowledge on SARS-CoV-2. My training in infectious diseases and immunology helped me understand the science outside of my specialty, but one of the most revealing mediums I found was #epitwitter — a group of epidemiologists on Twitter discussing in real time their findings, the findings of others, ideas, and where the science was going.

They would say, “Hey this paper came out today and this is significant.” You could see from the minds of about 80 people where the most important papers were in the field and what the collective mind was thinking. It’s an incredible opportunity to watch some of these amazing virologists, epidemiologists, and public health experts all coalesce on a single problem and then take that information and put it into something that’s relevant.

In your blogs, you use math to illustrate what happens in different social situations, adding the variable of time. How does time influence risk?

I was more attuned to this is because I do infectious dose work quite regularly in my lab. When we do experiments with animals, there is a really strong factor with dose and time. You can give high dose over a short period and the result is severe disease. You can give a low dose over an extended period and end up in the same situation, and then there’s everything in between. So exposure is not this one-off circumstance. Exposure can come in many different ways, and there are even more nuances. There are different infectious doses that happen between your eyes, your nose, and your lungs that affect things differently. We do the same thing with animals. If you give a dose intranasally, it’s very different from just putting it into the air for an extended period of time.

I was very interested in dose-time, and I didn’t think most of the general public was aware that that was an important factor. People were having a hard time trying to understand contact tracing situations. You might be contacted if you had been in contact with an infectious person and speaking with them for 10 or 15 minutes, but they didn’t know why. Why not 5 minutes? Why did it matter if you were in the same environment as them for a half hour or an hour, but not 15 minutes?

When I was able to put all that together — that it’s exposure to virus and time, you get to the same results by different pathways — I think the light went on for a lot of people. This is why splashguards went up in grocery stores. This is why the bus drivers are getting sick in NYC, because they are getting a low dose over an extended period of time. So it started to make sense to everyone about why we are being told to do things or not do things and how it related to the biology.

What does that mean for reopening businesses? For example, restaurants or movie theatres may try to make the environment safer by having fewer tables or selling fewer seats. Will that work, if people are still spending

2 hours together?

For every extra body you take out of a room, you are lowering the risk that somebody infected is in there to start off with. Then assuming that someone in that environment is infected, there is a gradient of respiratory droplets from that person that radiates out. So, certainly, having people spread out more in enclosed environments is an important way to reduce infection, but it’s not the solution to controlling all infections. Having a restaurant at half capacity that is still enclosed and has no or very little air exchange is going to be just as risky, but to fewer people.

For the medical community, fall is the start of the medical conference season. People who plan to attend these conferences are thinking about flying. You wrote a blog recently on Flying in the Age of COVID-19. We’ve heard stories of people taking off their masks once they are on board. Is flying too risky?

The cabin of a plane is almost as good as you can get for an indoor environment. Your biggest risk on the flight is not the person in front or behind you, it’s the person beside you that you strike up a conversation with. That’s a face-to-face conversation from very close, so in a very short period of time, infection can occur. Just understanding where the risks are and behaving appropriately is important if you are going to fly. Your risks are those people immediately around you and surfaces you touch, going to bathrooms, things like that.With regard to masks on flights, the longer the mask can stay on the lower the respiratory emissions from that person. Taking a mask off for short periods of time to eat or drink does increase the risk, but if the mask is worn the rest of the time, this balances out.

What frustrates me is that the mask is not really for you, it’s for everyone who is around you. They’re protecting you and you’re protecting them — it’s a bit of a social contract that you have when you are flying. If airlines are requiring you to wear masks, they shouldn’t be removed. People should understand that if you are going to fly — to get into these close-quartered spaces, we need to reduce harm as much as we can, and do our part. If you are flying from places that have a high prevalence of infection and going to a place where hundreds of people will be gathering in the same space, you may just be tempting fate. Not only do you run the risk of becoming infected from the flight itself and all the associated activities — departure, arrival, baggage claim, transportation, etc — but you are going to be sitting in an environment with colleagues for hours on end.

And if you are infected 1 to 3 days after your flight, then we have a much larger problem. It’s no longer just you. It’s everyone you are there with. So these things need a lot of thought before we embark on this type of event again.

In one of your blogs you advocate dropping the term “social distancing.” Why is that?

Along with many epidemiologists, I’ve been trying to change the term from social distancing to physical distancing. It’s a small change but it makes a big difference. It’s not about being disconnected socially from the people around you — it’s creating a physical space between people that is almost too far for the virus to be transmitted. That’s the basis of the 6 feet. The vast majority of respiratory emissions will drop and land at the feet of someone 6 feet away, whereas many will hit their face and chest of a person only 3 feet away. Creating physical distance — not becoming socially isolated — is the goal of these mitigation strategies. If I’m standing 10 feet from somebody across my lawn, I’m having social interaction but I still have the physical distance I need to be safe. The closer you are, the more dangerous it is.

What are the biggest misunderstandings right now driving people’s behavior when outside of the home?

Masks are a big misunderstanding at the moment. Because we have this idea that masks were made to protect the wearer, people have had a hard time adopting the idea that masks are an important part of the control of infection when you can’t physically distance. And the narrative that got mixed up from the CDC in the effort to try to protect PPE for healthcare workers only added to the confusion that we have now in society. When you add politics on top of that, it’s become a silly debate when we know it has an effect. That’s disappointing to me.

The CDC has done it again with changing fomites from being a risk to not being a risk in a period of a week and a half. Data doesn’t change that quickly, but we were all scratching our heads about why they lowered the risk of fomite transmission. We knew it wasn’t the primary driver but it was there. They put it in the same category as cats and dogs, and that just confused everyone in public health. Where’s the data that helped make that decision?Now they’ve moved it back, saying they didn’t mean to add to the confusion. But now we’ve had a week of dialogue where surfaces aren’t as important.

Because this is so new [to the USA] and we don’t have a history of widespread epidemics of infectious diseases in recent memory, we don’t really know how to react and behave correctly as a society yet. Other countries that are scarred by their history, like Hong Kong and Taiwan, were able to jump straight into it and get control very quickly because the general population already knew the behaviors they needed to do in order to limit the spread of the virus.

We are the infants in all this. We are still learning and that’s been hard. People need to understand that masks have a role, and surfaces have a role, and that all the things that we’ve been discussing — enclosed spaces, long time, etc, all have their part in controlling the trajectory of what happens over the next few weeks, months, or year — whatever we are dealing with now.

What mistakes are we making in our early efforts to open up?

My biggest fear is opening without a plan. If you read my blogs, it’s all about planning. Give people the tools they need to make the best decisions/choices for themselves and their families in the risks they face and the ways they can reduce them.

I’m finding that a certain group of people are rushing to open and maybe haven’t thought it through enough. I’m fortunate to work with people who are really thinking about how to reopen and do it as safely as they possible can. Even though they were given the green light to open last week, they chose not to until they had systems in place to protect not only their workers but their guests.

Erin S. Bromage, PhD, is an associate professor of biology at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, where he teaches courses in immunology and infectious disease. Dr Bromage’s research focuses on the evolution of the immune system, the immunological mechanisms responsible for protection from infectious disease, and the design and use of vaccines to control infectious disease in animals. He also focuses on designing diagnostic tools to detect biological and chemical threats in the environment in real-time.

6/8/2020

The protests over George Floyd’s murder will likely exacerbate the second wave of infection we are already seeing. I wish the timing had been different. I would have been out, protesting with all the non-violent young people I saw in my hometown. I chose to stay safe and avoid overwhelming my colleagues, nurses and staff at our straining hospitals.

As other countries’ experiences are reported, the clear winners are Taiwan (7 deaths) and Japan (900+ deaths). The latter didn’t do much testing. They drilled into people wearing PPE and the three Cs: avoid Closed spaces, Crowded spaces and Close contact.

Here is an article arguing that we could have followed Sweden’s approach. The subtitle could be “Let it rip.”

If We All Get COVID Anyway, Should We Just Get It Over With?

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE. Medscape June 5th 2020

“Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson at the Yale School of Medicine. In the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, the phrase “flatten the curve” got into the national zeitgeist. By shutting down large aspects of society and implementing social distancing and other public health measures, we would slow the spread of the coronavirus to avoid overwhelming our hospital system. Grim stories from Italy of triaging ventilators and patients dying in corridors made the problem that much more real.

And so far, it seems we have flattened the curve. We have not had to deny life-saving treatments because ventilators or ICU beds were not available. This was due in no small part to herculean efforts by healthcare workers to expand capacity, but also to the efforts of everyday Americans who took the precautions seriously. But one question has been sitting in the back of my mind since the talk of curve-flattening started: Does everyone get the coronavirus eventually? It’s an important question. This is a novel virus for which none of us are likely to have any existing immunity. We are ripe for infection, and the rate of spread (without social distancing) is rapid. The presence of asymptomatic spread makes the situation even worse.

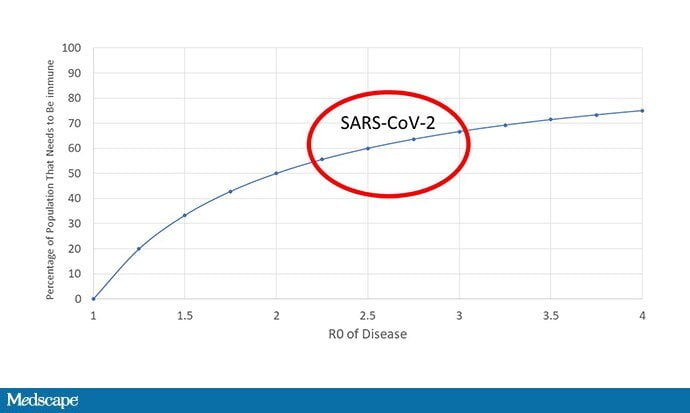

Of course, the more people get it, the more people become immune and the harder it is for the virus to continue to spread. The equation to calculate the percentage of the population that needs to be immune to confer broad herd immunity is pretty straightforward: it’s 1 – 1/R0. If each person with the disease infects three others, then once two out of three people are immune, the disease doesn’t have enough targets to keep spreading. I made a graph showing the relationship between the R0 and the population percentage necessary to confer herd immunity here.

For COVID-19, we probably have to have 65%-70% of the population immune before the thing dies out. I’ll just point out that we are nowhere close to that. Even in New York City, the American epicenter of the disease, seroprevalence studies suggest that only about 25% of the population is immune. If our battle against coronavirus is a baseball game, we’re somewhere in the second inning.

But if 65% of us are going to get it eventually, then you can make a particularly utilitarian and somewhat strange argument about our public health measures: Maybe we should flatten the curve just enough to avoid overwhelming our hospitals, but no more. Get through this as quickly as possible without leading to excess deaths. It even gives a quantifiable metric to score the government’s response: As long as a single person doesn’t get denied care because of hospital overcrowding, it’s a victory. There’s a lot that’s appealing about this argument. But I want to deconstruct it a bit from a practical, epidemiologic, and ethical perspective.

First, the practical. Delaying the spread of the disease doesn’t only help hospitals cope with surges; it also buys us time to do medical research, identify treatments, and find vaccines. And I want to point out that this isn’t all pie-in-the-sky, maybe we’ll have a large randomized clinical trial of a new drug. This is highly practical stuff as we figure out how to treat COVID-19. Think of how much we’ve learned in these few months—about the utility of proning, about delay of intubation, about the risk of thrombosis—that are changing how we care for these patients. You’re way better off getting sick from coronavirus now than you were in March.

Another practical issue is that there is really no way to skirt just under overwhelming our hospitals. We can’t just dial up and dial down the disease spread; it is different in different places and substantially lags policy choices. There’s also a stochastic element here: Outbreaks will happen and they will not be predictable.

Second, the epidemiologic. It turns out that outbreaks don’t just stop when you reach herd immunity. They have inertia. Here’s Dr Albert Ko, chair of Yale’s Department of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases:

Finally, the ethical. Even if we assume that the total death rate is the same (which I hope at this point that I’ve convinced you is not the case), compressing those deaths into a shorter period of time still robs people of life. I mean, look—100% of people die eventually. As physicians, the war against death is one we will always lose. But we fight the battle to push that day as far into the future as possible. I think we need to keep that in mind as we continue to struggle with COVID-19. Every day is a victory.”

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Program of Applied Translational Research. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @methodsmanmd and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com.

6/1/2020

We are all getting tired of COVID-19 news. Here is a brief respite; yet, it is still relevant:

“The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not sufficient warrant… The greatest orators study their adversary’s case as well as their own… He who only knows only his own side of his case knows little of that.” John Stuart Mill.

5/25/2020

What facts are you looking at to form an opinion on COVID-19? For example, what do you think about wearing masks?

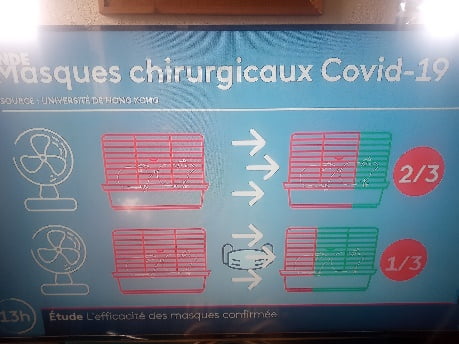

Take a look at this image on how efficient masks are. It was shown on French TV May 18th 2020. The study was conducted in Hong Kong

Basically, no masks result in 2/3 of exposed mice to get infected. Wearing masks reduces the infection rate by half.

Now consider this:

“If men lived under the guidance of reason… no injury would be done to his neighbor. But seeing that he is pray to his emotions… he is often at variance with one another.” Spinoza

“In psychology, Slovic says, there’s a phrase called “unmotivated cognition: the psychological realm that shows how people kind of spin the information and the arguments in ways that give them the answers that they want.” Feelings, in many ways, overpower facts. “We interpret the facts to help us feel good, to feel virtuous, to feel, you know, that we’re doing the right thing,” Slovic says. “Those of us who study the psychology of risk and decision-making, we used to think that everyone went around like, you know, with calculators in their brains calculating the costs and benefits like the Office of Management and Budget does. But we do those calculations in our brain in milliseconds through firing of neurons that create feelings in us,” he continues. “So our feelings are the compass that guides us through our day. We assess things and we make trade-offs.” Dr. Paul Slovic, a University of Oregon psychologist who studies risk perception. Salt Lake Tribune May 17th 2020.

Selfishness not the same as liberty. George Pyle, Salt Lake Tribune.

“Today we are faced with a threat of a viral pandemic that, if not properly addressed by governments and citizens alike, has every capability of killing millions of us. There is every reason to hope that we would be able to break the back of this threat if we would heed the advice of experts and give up some of our creature comforts for a while. Sadly, the idea of individuals making any kind of sacrifice for the public good has come, in some circles, to be known as tyranny. We have a concept of liberty based on acting selfishly and being quite willing for the old, the sick and the poor to lay down their lives so heavily armed fat white men can order a footlong without the intolerable indignity of wearing a mask. If they were real patriots, willing to sacrifice their own well-being for others, that would be great. But their behavior only threatens both themselves and others.”

Stay-at-home orders saved lives of nearly 250,000 in 30 largest U.S. cities

The Hill (5/18, Wilson) reports, “A new analysis says nearly 250,000 people in the nation’s 30 largest cities are alive today because of strict stay-at-home orders issued by local and state governments.” The report is “from the Urban Health Collaborative at the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel University,” and it “found the stay-at-home orders likely reduced the number of coronavirus deaths by 232,878, and prevented 2.1 million people from requiring hospitalization.” This “analysis calculated the number of deaths caused by the coronavirus versus a model compiled by mathematicians…that showed what might have happened had Americans not taken the drastic social distancing steps that governors and local elected officials have ordered and encouraged over the last few months.”

05/18/2020

Post Pandemic Presages.

*Economy: it will be different, hopefully less driven by consumerism. Working from home is here to stay.

* Society: will we learn to put relationships first?

* Animals: we are mistreating them with grave consequences to ourselves, the planet, and of course animals themselves. Viruses mutate in them when they are crowded and fed antibiotics and steroids. There will be other pandemics if we don’t mend our ways. The resources used to feed one meat-eater could feed 70 vegans. Do the math. Check out this book:

I know, I already posted it. But did you read it?

I know, I already posted it. But did you read it?

Our future may depend on it.

Numbers to Ponder

- We need to test 5 million people a day and follow up with contact tracing to imitate successful countries like Germany and South Korea. Otherwise we have to wait for vaccine and/or 2/3 of people to get infected to end threat

- People infected are 10x higher than reported

- ¼- ½ of infected people are asymptomatic

- Regular Flu mortality is 0.1%. Covid-19 I 0.6%

05/11/2020

At the beginning of the pandemic many of us thought that it would be much like the common Flu because we wanted to be reassured in the face of many unanswered questions. Some of them have been answered:

In 5 weeks, New York City has had the same number of deaths from the common Flu it had in the last 5 years. So, “Don’t Die of Stupid.” Stay home if you can afford it. If you cannot, I feel bad for you. I get it—you need to make $. Be as safe as possible going back to work. Practice social distancing and wear PPE. In flaunting your liberty, be mindful of the medical people you may be overtaxing if you wind up in a crowded hospital. BTW, the economy will not reopen until the 2/3 of Americans who take the pandemic seriously feel safe to go back out to your restaurants, salons, movies, and stores. It will be a while before I venture out. I am waiting for a better antibody test, herd immunity (>60% of people infected) and, or a vaccine.

THIS IS NOT A HOAX. The refrigerated trucks full of corpses in NYC are very real. Remember that young people are dying, too. We will soon see a second wave that will take more children with a Kawasaki-like syndrome.

What can you do to improve your chances of beating the virus if infected? Stop eating so much sugar. It depresses the immune system. This is a big reason why African Americans and Latinos are disproportionally affected. Yet, this is not talked about in the media at all. They do list other valid factors: crowded living conditions, essential jobs, poor access to health care, no insurance and systemic inequalities.

05/02/2020

The bad news: the pandemic is likely to go on for 18 more months. There will be a second wave and perhaps a third, just like the Spanish flu. Two thirds of Americans must get infected for our society to develop an immunity. A good many of us will die in the process. The questions we had in January are finally being answered. Epidemiologists suspected this grim news, but they wisely refrained from scaring us at the beginning. But after three months, most people have come to intuit we are in for a long ride.

The good news: we still have tools to cope with. If you can afford it, stay home, continue social distancing even as stores and restaurants open back up. Wear a mask. Help our governments help us by getting tested and complying with contact-tracing mandates. Stop eating so much sugar while cocooned at home—it suppresses the immune system. Get out to exercise or just go for a walk. When the antibody test is ready for marketing, get it to see if you have developed an immunity, even though it may not give us a definite assurance of avoiding a second infection.

Given the facts, I believe the benefits of a vaccine, said to be ready in January and the fodder of conspiracy theorists, far outweigh the cost. This is why India will administer it next month, skipping Phase III. It is a mistake because the vaccine may make reinfections worse by rendering recipients more sensitive to the COVID-19. In fact, we may not get a vaccine at all. Remember that HIV and Hepatitis C viruses don’t have them.

For a comprehensive review of the developing COVID-19 vaccine, read this excellent article by ANDY LARSEN published recently in the Salt Lake Tribune:

A coronavirus vaccine Q&A: How would it work?

I’m not sure I’ve read a phrase more often over the past two months than “until there’s a vaccine.” We are now preparing to take small steps toward our old lives. We’re letting some businesses reopen, allowing people to return to state and national parks, and more — but we are also starting to accept that the coronavirus won’t be eliminated anytime soon. Until there’s a vaccine, our world will be different.

Face masks will become ubiquitous, indoor sports arenas and big theaters will likely stay closed, and dozens of businesses will be limited, leaving many out of work. That’s the impact for the healthy.

Until there’s a vaccine, those who are elderly or have preexisting conditions will live vastly limited lives or be in significant danger. Remember how obesity was the condition with the strongest tie to critical illness in coronavirus patients in New York City? Well, 42.2% of American adults are obese. And about 1 in 7 Americans, 15.2%, are over age 65.

You’ve probably heard that a vaccine is 12 to 18 months away, but is that really true? Also, how do they work? How do we test them? Can we speed up the process? And what can we do in the meantime?

We all have a stake in this, so let’s try to answer these vital questions.

How do vaccines work?

Vaccines are cool. Essentially, a vaccine is a substance that to the body’s immune system appears like a disease-causing microorganism, like a bacteria or virus. When you inject someone with the vaccine, the immune system learns about the form of the microorganism, then remembers it. That way, the body can immediately kill the microorganism whenever it encounters it in the future, without being fooled or caught off guard in the early stages of infection.

There are a bunch of different ways to make something look like a specific microorganism. The simplest way is to just take some of the disease-causing germ and kill it with heat or chemicals — those vaccines are called inactivated vaccines, and that’s how the polio vaccine works. Another way is to use a particularly weak or even harmless version of the virus — those are called live-attenuated vaccines. This is how the measles vaccine works.

We eventually realized that, in some cases, you could just take part of the microorganism, combine it with something safe, and inject that. Those are called subunit vaccines, and there are a whole bunch of different types. Vaccines for hepatitis, tetanus, and HPV are examples of subunit vaccines.

In the past 20 years, we’ve been working on DNA and RNA vaccines. You’ve probably heard of DNA — it’s the genetic code in your cells, the set of instructions that makes you, you. RNA is essential in turning the DNA code into the proteins that make everything happen in your body. By injecting this DNA or RNA into someone, we can warn the immune system about this code, and have it fight off anything with that code in the future. It should also provide real advantages in terms of production and safety.

DNA and RNA vaccines are new, though: There are no approved DNA or RNA vaccines for human use in the United States. We’ve gotten close with SARS in 2003, bird flu in 2005, swine flu in 2009, and Zika in 2016. We’ve even done trials on an HIV vaccine with these methods.

We also haven’t ever made a vaccine for any coronavirus. Again, we’ve gotten close with SARS and MERS, so scientists are optimistic. But because funding seems to dry up for vaccines late in the process, we haven’t gotten across the finish line, and we’re starting a bit behind. This is one failure of our worldwide health care system.

How are vaccines tested?

Once scientists get a good idea for a vaccine, they’re widely tested in animals in the preclinical stage, “looking at whether it works and what dose works best. Testing on mice is common, but this coronavirus doesn’t grow in mice. Testing on an animal more similar to humans, like rhesus macaque monkeys, gives us a better idea.

Then we move to a three-phase process. Phase I studies are done on a small number of volunteers to see how effective the vaccine is in humans and whether it is safe. These volunteers are closely monitored. Phase II studies are larger and consist of several hundred people. Here, safety, effectiveness, dosage, delivery method, and delivery schedule are tested.

Finally, Phase III is the largest study — thousands or tens of thousands of volunteers are used in a study that is randomized, double- blind, with a control group and everything. The vaccine maker is looking for rare side effects at this point.

If everything goes well and is approved by the FDA, vaccine production can start. From 2006 to 2015, only about 16% of vaccines made it from Phase I to approval, 24% from Phase II to approval, and 76% from Phase III to approval. Keep that in mind.

Can we fast-track vaccines?

This whole process usually takes five to 10 years. In the case of this coronavirus, we’re trying to get it done in 12 to 18 months… or faster.

There are things we can do to speed up the process. One is to work in parallel — to, for example, create vaccine production systems even before the tests are complete. That way, we’re not wasting time on construction. Microsoft founder Bill Gates is at the head of some of these efforts.

Another is challenge testing. Normally, vaccine studies involve giving a volunteer a vaccine, then allowing the person to be exposed — or not — to the virus na tu r a lly. There are a whole lot of participants who don’t end up getting exposed, making them kind of worthless for the experiment. This means experiments need more people and take more time.

But in this pandemic, every extra day means thousands of additional people die worldwide. So instead, “challenge testing” actually exposes volunteers to the virus in a lab, allowing researchers to find out much more quickly if a vaccine works. It’s normally considered unethical, but many are arguing that challenge testing would save huge numbers of lives.

And the coronavirus might be a relatively good candidate for challenge testing anyway: because young people die so rarely from the disease, there’s a natural body of challengees.

That’s the idea behind an organization called 1DaySooner, which is putting together a list of volunteers willing to be infected to advance vaccine development. So far, more than 4,000 people have signed up.

What vaccines are being tested now?

As of April 8, there were 115 vaccine candidates in process, according to Nature. Seven of those had made it to human testing. Here is a look at their status, with major help from Science magazine’s Derek Lowe. (Note: He is not the former Red Sox pitcher.) Oxford University’s “ChAdOx1- nCov19” vaccine is a DNA vaccine which worked well in monkeys. Researchers are combining their Phase I and Phase II into one large study with multiple “endpoints,” or places the study can stop if things go poorly. They’re saying their Phase III testing could start “at the end of next month,” and if that goes well, they could have a few million doses of their vaccine by September. Wow.

Both the U.K. and the Netherlands have started manufacturing plants for this vaccine in case testing goes well, spending millions of dollars. However, there isn’t yet a North American manufacturing partner. If our government wants to speed up vaccine production, spending money on this one seems like a worthwhile gamble.

CanSino Bio’s “Ad5-nCoV” vaccine out of China also uses the DNA method. Researchers advanced it to Phase II already, based on preliminary results in Phase I testing. The vaccine worked well on monkeys, but the company hasn’t made the results of early human testing public yet.

As Lowe notes of the two Phase II candidates, “there is literally no way to know which of these competing efforts will yield a better vaccine, or if either will work at all” U . S . – b a s e d Mo d e r n a ’ s mRNA1273 vaccine is an RNA vaccine that is currently in Phase I, with Phase II slated for “second quarter 2020.” The Phase I testing includes two injections, with a second shot being administered about a month after the first. That second shot was just given last week to volunteers in Seattle and Atlanta.

Philadelphia- based Inovio’s INO-4800 vaccine is a DNA vaccine that began Phase I testing on 40 patients in April. The fun quirk about this one is that it uses a new method called a “Prickly Patch” to deliver the vaccine: It’s a fingertip- sized patch with teensy pointers made of sugar and the vaccine. You put it on your skin, and the moisture from your skin dissolves the sugar and delivers the vaccine to your skin cells. It propagates through your body from there.

Germany’s BioNTech and U.S.based Pfizer are teaming up to test four different RNA vaccines at once. They’ve also received clearance to do a combined Phase I/II trial at the same time with these vaccines, which has started in Germany and could start in the U.S. next week with federal approval. They say they could produce “millions” of doses by the end of 2020 if things go well, and “hundreds of millions” in 2021.

China-based Sinovac’s PiCo-Vacc vaccine is an old-school inactivated virus vaccine, which also will probably need a booster. But a simple approach may prove effective and has had encouraging results in monkey testing with this coronavirus. It has been approved for human testing.

The Wuhan Institute of Biological Products is also making an inactivated- virus vaccine, but there’s little public information available.

Remember: It is likely that most of these candidates will fail, but it’s good that we’re trying multiple approaches with multiple delivery systems. A first vaccine will “win the race,” but creating many successful vaccines may allow us to get more doses to more people faster. Variety also gives us the advantage of using the best vaccine for each use-case.

Given that the U.S. hasn’t found a manufacturing partner for the Oxford vaccine, which seems to be furthest along, I’d say the fourth quarter of 2020 or the first quarter of 2021 are the best-case scenarios for actually being able to use these early vaccine candidates if they are successful.

The rollout will take some time, too. Even if millions of doses are produced then, the first to be vaccinated will be health care workers and the most vulnerable.

What do we do until then?

Well, from a scientific point of view, we work on treatments.

One that has had impressive effectiveness in limited trials so far is plasma therapy. This is stupid- simple science: Since recovered COVID-19 patients have immune systems that have created antibodies for the virus, why not just extract some of their blood and put it in sick people? That way they’ll have the antibodies, too! This has been used since the 1800s.

Cynthia Lemus, a 24-year-old flight attendant from Magna, was the first person in Utah to be treated in this way by Intermountain Healthcare about a week ago.

The problem is that plasma is pretty variable depending on the source, and that can mean “good batches” and “bad batches” of plasma. Blood plasma transfusions can also result in some nasty side effects, like allergic reactions to the plasma given. There may not be much plasma available in the early days of an up-swinging pandemic. And finally, these antibodies don’t provide immunity; someone could still be infected again down the road.

There are hundreds of studies underway on plasma therapy and other treatments. Until there’s a vaccine, they are our best shot at saving lives. Ah, there’s that phrase again. “Until there’s a vaccine” — a reminder of a future where our lives return to normal, a reminder we’re still so far away.”

04/25/2020

Loss of jobs and closure of small businesses are valid concerns to all of us. But going back to work too early will trigger another wave of infection, as proven by Singapore. One third of the country is willing to run the risk of infection and death to themselves and others. The rest is willing to wait for proof of immunity with antibody testing and aggressive testing for infection, followed by isolation and monitoring of contacts. The latter is amply supported by science, which I believe should be our main source of information.

I am sorry, but opening restaurants and small shops will not bring most of the public in. Most people will be scared for a while. I just watched the French news: restaurants are pretty empty after resuming business. They are resorting to deliveries and drive-throughs to survive, which is what we are already doing.

A vaccine and proof of immunity with antibody testing are not ready for marketing, although the latter should be available within weeks. The former is already raising concerns among conspiracy theorists and anti-vaccine advocates. No doubt there is some truth in their arguments (see vaccine blog). It boils down to a cost-benefit analysis. In the case of the common flu, the benefit of a vaccine is low compared to cost. It is the opposite with COVID-19. Doctors understand this sort of analysis, the reason why only one half of them get the common flu vaccine. BUT I assure you, they, including me, will be getting the COVID-19 vaccine.

04/20/2020

Here is the good news: the number of people infected is about 6-30X underestimated. This tells us it is tolerated by most people rather well, making its death rate ~0.1%, much like the common flu.

Here is the bad news: COVID-19 is much more contagious and it has already killed in three months the same number of people the common flu does in one whole year. And this is so even when we have been quarantined for the former, which we have never done with the latter.

I understand the need to get back to work, but vulnerable people, if possible, should stay home until we have a vaccine (more on this next week) or they have been proven immune with an antibody test. Those who feel our governments cannot keep us quarantined forever have a valid point. They have a right to determine their own fate. But that right stops where it may infringe harm to others. Sure, not working is harmful, too, but dying from it is far-fetched when governments are passing out free food.

So, what do we do? How about this: go back to work if you must, but we aware that our overwhelmed doctors and nurses are on their knees, overwhelmed, begging you to stay home. Do they have rights too? What if they refused to take care of you if you end up unable to breathe in their ER? They have a right to go home if they are exhausted and infected. What if they told you they don’t have enough staff, nor beds or ventilators for you? Will you be OK if they point to a crummy bed for you in the parking lot? Are you ready for one or more waves of infections? Our health care system is not. I am not.

04/13/2020

COVID-19 is affecting people with a depressed immune system the most. The media has finally reported more specific information: as suspected, it is the obese and the poor that are most vulnerable and most commonly affected. (Those with asthma, arthritis, other immune problems and the elderly are also affected, of course).

Typical of the present medical paradigm, this sad fact is chalked up to minorities, people of color “lacking medical care.” No, what they lack is proper nutrition and healthier environments! They HAVE to eat too much sugar and not enough veggies because that is all they can afford. Processed diets destabilize their immune system/gut microbiome. They also live in blighted neighborhoods bereft of grocery stores with fresh produce, but, redolent with crime. Most of them cannot work virtually. Worse, they have to ride crowded public transportation where it is a lot easier to catch the virus. They are stressed out. Stress depresses the immune system. So does air pollution and poor sanitation. If they had “proper medical care,” they would be taking a pill for diabetes, arthritis, high blood pressure, etc., and they would still live in those unhealthy conditions. They would still have a poor immune system and metabolism, two integrated systems, as the whole body is.

References

Public state data indicate African Americans may be disproportionately affected by COVID-19

STAT (4/6, Cooney) reports, “Stark statistics are coming to light only now and only in piecemeal fashion showing that African Americans are disproportionately affected by [COVID-19].” For example, African Americans in Illinois “accounted for 29% of confirmed cases and 41% of deaths as of Monday morning, yet they make up only 15% of the state’s population, according to the Illinois Department of Public Health.” Michigan data “mirrors Illinois, with 34% of [COVID-19] cases and 40% of deaths striking African Americans, even though only 14% of Michigan’s population is Black.”

People with long-term exposure to air pollution are more likely to die from coronavirus

The New York Times (4/7, Friedman) reports “researchers at the Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health” conducted “an analysis of 3,080 counties in the” U.S. and concluded that people with coronavirus “in areas that had high levels of air pollution before the pandemic are far more likely to die from the infection than patients in cleaner parts of the country.” According to the Times, this is “the first clear link between long-term exposure to pollution and [COVID-19] death rates,” although “for weeks, public health officials have surmised a link between dirty air and death or serious illness from [COVID-19], which is caused by the coronavirus.” The Hill (4/7, Bowden) reports the researchers concluded, “A small increase in long-term exposure to [particulate matter] leads to a large increase in COVID-19 death rate, with the magnitude of increase 20 times that observed for [particulate matter] and all cause mortality. The study results underscore the importance of continuing to enforce existing air pollution regulations to protect human health both during and after the COVID-19 crisis.”

“Pursuit of death” during pandemic?

“The true disciple of philosophy is likely to be misunderstood by other men; they do not perceive that he is ever pursuing death and dying; and if this is true, why, having had the desire of death all his life long, should he repine at the arrival of that which he has been always pursuing?” Plato, Phaedo.”

Please, don’t misunderstand. This is not about a morbid, unhealthy desire to cross the river Styx. Read on with an open mind.

“And will [the philosopher] think much of the other ways of indulging the body, the acquisition of costly raiment, or sandals or other adornments of the body? Instead of caring about them, does he not rather despise anything more than nature needs? I should say that the true philosopher would despise them… Would you not say that [the philosopher] is entirely concerned with the soul and not with the body? He would like, as far as he can, to be quit of the body and turn to the soul… the soul runs away from the body and desires to be alone and by herself… He who thinks nothing of bodily pleasures is almost as though he were dead… The mind is gathered unto itself and [material things do not] trouble her, neither sounds not sights nor pain nor pleasure… she has little to do with the body… but is aspiring after being. The body introduces a turmoil and confusion and fear into the course of speculation, and hinders from seeing the truth, and all experience shows that if we would have pure knowledge of anything we must be quit of the body.”

04/06/2020

Three issues that are brought up on a regular basis:

- “It seems the COVID-19 numbers don’t add up. It is not as deadly as we are being told. The common flu kills a lot more people, yet we don’t hear much about it.”

- “COVID-19 is a weaponized bug designed to kill a lot of people and ruin the economy.”

- “Life after COVID-19 will be much different than what we have known.”

Yes, the numbers of patients infected with COVID are less than the common flu and arguably less deadly, SO FAR. Being a new virus, we don’t have all the answers, neither do we have a vaccine or mitigating treatment. So, it pays to be cautious.

The reason we don’t hear about the common flu killing more people is because our hospitals were already near capacity with patients suffering and dying from it. Being that our health care system is driven by profits, it has not had extra capacity sitting idle to accommodate a pandemic. It would have been “a waste of resources,” according to bean counters. So, the extra demand from COVID-19 found the system with its pants down.

So, yes, the numbers do point to COVID-19 being a mild infection. BUT, unfortunately it is fatal in some people, especially the elderly and those suffering from chronic diseases. When the system is at the brink of collapse, WE NEED TO STAY HOME! Do it for the love of medical staff, your old-timers, if not for yourself. Don’t be selfish. About 15-20% of our doctors and nurses are already infected. The hospitals they unselfishly staff in big cities are collapsing under the strain. They fear for their lives and their loved ones. They are begging us to stay home because they are running out of PPEs, ventilators, resources, strength and hope.

LET’S GIVE THEM A BREAK!

There are many conspiracy theories about the origin of COVID-19. To think that it is a weaponized bug designed to cull the population and ruin the economy is illogical. It contradicts the argument discussed above: If one believes that the numbers point to a mild infection, then that is a pretty weak weapon. There are rumors that research money from the National Institute of Health at University of North Carolina/Chappell Hill had a hand in creating a chimera version of the common corona cold virus. A Chinese scientist may have taken that research to Wuhan to develop the virus further. Yes, all big nations are engaged in bioengineering.

COVID-19 got away from an experimental Wuhan bioengineering facility because some idiot sold the bats and snakes they used for experimentation to a wet market of animals. I believe there is plenty of evidence it propagated from there to the general public. Many other countries, including the USA, also abuse/mistreat animals for consumption in markets where they are kept alive to be butchered before/after purchase. It is a US$18 Billion industry.

The point is still the same: our health care system is collapsing, regardless of where the damn bug came from. Our doctors and nurses are at the end of their rope screaming for help while conspiracy idiots sit comfortably at home casting stones at a system they hate and speculating about who to blame. This is like pointing fingers when the house is burning down. Sure, I see the health care system’s flaws, too. Who does not? It is the best and only system we have to deal with acute problems!

Mistreating animals is cruel and immoral. We need to also look at industrial farming of animals. It can be just as cruel. Animals are kept in crowded conditions, fed steroids, growth hormone and filled with antibiotics. More than half of antibiotics made are fed to animals. What do you think it does to their microbiome—and ours? It is only a skip and a jump from there to mutating organisms infecting us.

Do you believe a pig, a chicken, a cow, are devoid of feelings? Two thirds of Americans own a pet. We know they have feelings. So do the animals we eat. Would you eat your dog? It is time to consider becoming a vegan, especially with the advent of technology that grows meat in laboratories and produces plant-based BEYOND MEAT. With the resources used to feed one carnivore, we could feed 70 vegans. Think on the impact on the planet. And the economy. And animals. And our very lives…

I hope the COVID-19 Pandemic ushers in a new age of kindness to animals.

I hope it leads to more openness on how our money is used for secret military purposes and genetic engineering.

For sure it will lead to more telemedicine, closer relationships with our loved ones, a baby boom in nine months, and I hope, less consumerism.

References

Engineered bat virus stirs debate over risky research- Lab-made coronavirus related to SARS can infect human cells.

J. Nature Nov 2015, doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18787

“Editors’ note, March 2020: We are aware that this story is being used as the basis for unverified theories that the novel coronavirus causing COVID-19 was engineered. There is no evidence that this is true; scientists believe that an animal is the most likely source of the coronavirus.

An experiment that created a hybrid version of a bat coronavirus — one related to the virus that causes SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) — has triggered renewed debate over whether engineering lab variants of viruses with possible pandemic potential is worth the risks. In an article published in Nature Medicine1 on 9 November, scientists investigated a virus called SHC014, which is found in horseshoe bats in China. The researchers created a chimaeric virus, made up of a surface protein of SHC014 and the backbone of a SARS virus that had been adapted to grow in mice and to mimic human disease. The chimaera infected human airway cells — proving that the surface protein of SHC014 has the necessary structure to bind to a key receptor on the cells and to infect them. It also caused disease in mice, but did not kill them. Although almost all coronaviruses isolated from bats have not been able to bind to the key human receptor, SHC014 is not the first that can do so. In 2013, researchers reported this ability for the first time in a different coronavirus isolated from the same bat population. The findings reinforce suspicions that bat coronaviruses capable of directly infecting humans (rather than first needing to evolve in an intermediate animal host) may be more common than previously thought, the researchers say.

But other virologists question whether the information gleaned from the experiment justifies the potential risk. Although the extent of any risk is difficult to assess, Simon Wain-Hobson, a virologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, points out that the researchers have created a novel virus that “grows remarkably well” in human cells. “If the virus escaped, nobody could predict the trajectory,” he says.

The argument is essentially a rerun of the debate over whether to allow lab research that increases the virulence, ease of spread or host range of dangerous pathogens — what is known as ‘gain-of-function’ research. In October 2014, the US government imposed a moratorium on federal funding of such research on the viruses that cause SARS, influenza and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome, a deadly disease caused by a virus that sporadically jumps from camels to people).

The latest study was already under way before the US moratorium began, and the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) allowed it to proceed while it was under review by the agency, says Ralph Baric, an infectious-disease researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a co-author of the study. The NIH eventually concluded that the work was not so risky as to fall under the moratorium, he says.

But Wain-Hobson disapproves of the study because, he says, it provides little benefit, and reveals little about the risk that the wild SHC014 virus in bats poses to humans.

Other experiments in the study show that the virus in wild bats would need to evolve to pose any threat to humans — a change that may never happen, although it cannot be ruled out. Baric and his team reconstructed the wild virus from its genome sequence and found that it grew poorly in human cell cultures and caused no significant disease in mice.

“The only impact of this work is the creation, in a lab, of a new, non-natural risk,” agrees Richard Ebright, a molecular biologist and biodefence expert at Rutgers University in Piscataway, New Jersey. Both Ebright and Wain-Hobson are long-standing critics of gain-of-function research. In their paper, the study authors also concede that funders may think twice about allowing such experiments in the future. “Scientific review panels may deem similar studies building chimeric viruses based on circulating strains too risky to pursue,” they write, adding that discussion is needed as to “whether these types of chimeric virus studies warrant further investigation versus the inherent risks involved”.

But Baric and others say the research did have benefits. The study findings “move this virus from a candidate emerging pathogen to a clear and present danger”, says Peter Daszak, who co-authored the 2013 paper. Daszak is president of the EcoHealth Alliance, an international network of scientists, headquartered in New York City, that samples viruses from animals and people in emerging-diseases hotspots across the globe.

Studies testing hybrid viruses in human cell culture and animal models are limited in what they can say about the threat posed by a wild virus, Daszak agrees. But he argues that they can help indicate which pathogens should be prioritized for further research attention. Without the experiments, says Baric, the SHC014 virus would still be seen as not a threat. Previously, scientists had believed, on the basis of molecular modelling and other studies, that it should not be able to infect human cells. The latest work shows that the virus has already overcome critical barriers, such as being able to latch onto human receptors and efficiently infect human airway cells, he says. “I don’t think you can ignore that.” He plans to do further studies with the virus in non-human primates, which may yield data more relevant to humans.”

Permanently ban wildlife consumption

J. Science 27 Mar 2020:Vol. 367, Issue 6485, pp. 1434

“Although the origin of severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2 (SARSCoV-2)—the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—has not been identified, it is clear that China’s wildlife market played an important role in the early spread of the disease (“Mining coronavirus genomes for clues to the outbreak’s origins,” J. Cohen, News, 31 January, scim.ag/COVID-19genomeclues). On 24 February, China’s National People’s Congress adopted legislation banning the consumption of any field-harvested or captive-bred wildlife in an effort to prevent further public health threats until a revised wildlife protection law can be introduced. We argue that China needs to seize this opportunity and permanently ban wildlife consumption.